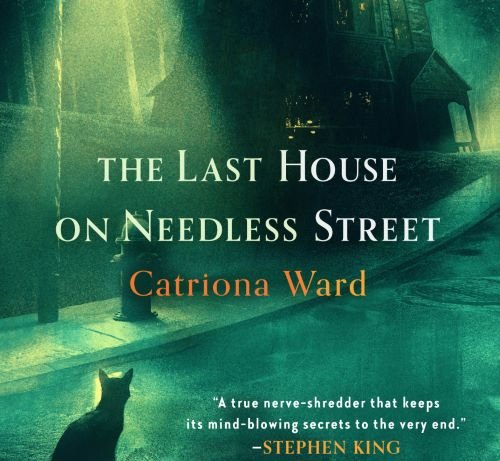

Book Review: The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward

The heartbeat of The Last House on Needless Street is discordance. Every character, setting, and arc is an askew, asymmetrical thing that shuffles at the edge of the reader’s perception showing a side that does not match its shadow. This is the unreliable narrator taken from element to thesis, and throughout my time with the novel I felt a deep discomfort which underpins all of the events that play out on the pages.

I experienced a monumental life event whilst reading Last House–the birth of my first child–and thus I did something I never do and read several reviews of the book before sitting down to write my own. I wanted to ensure I hadn’t missed some crucial detail, some pivotal element, some early plot point that my brain may not have absorbed during the wee hours spent sleepless on a hospital room’s couch under COVID quarantine. Never have I witnessed so many professional journalists collectively struggle to say something resonant about a book, to come up with an incisive thought that wasn’t some watered-down cliché or horror novel platitude. The Last House on Needless Street is a difficult title to digest, and I fear many readers will find it unsatisfying once they’ve swallowed (or purged, as may be the case) what lies between its covers. That’s not delivered here as a criticism, but rather a testimonial; Last House’s discordant world will linger in your mind, leaving you uneasy, whether you ultimately enjoy the book or not.

At the opening of this head game of a novel, Ted Bannerman, a thirty- or forty-something solitudinarian is living at the end of a cul-de-sac. Both his house and his body are in disrepair, and his only ventures outside are to the nearby woods where he venerates primordial “gods” of his deceased mother–buried totems that are never fully described–or to an off-exit bar where he mostly observes the comings and goings of the other lonely men who gather there. Occasionally, he uses an online dating site (and fake profile pictures) to lure women into meeting him, but the outcome of these dates isn’t something the reader gets to see firsthand. We know that there is never a second date.

The other denizens of Ted’s home are his cat, Olivia, who has regular perspective chapters throughout the novel, and his adolescent daughter, Lauren, whose visits with her father end abruptly and mysteriously. His relationship with each is volatile; Olivia sometimes being the targets of his alcohol-fueled ire and Lauren filling the role of his captive ward, one whose warmth toward her father is almost always an act of subterfuge designed to mask another escape attempt. Further in the background are some old, scratching ghosts in the attic, and the occasionally animated memory of his mother, a disgraced nurse who looms over Ted’s life even in death.

Whilst every scene in Ted’s home is something that literally happens, the reader will understand from the first page that they’re never quite getting the whole story, and this heavy burden of mistrust is what makes the novel so effective. A cycle of presentation and reinterpretation begins, as the events of the home are chronicled by one character and reenvisioned by another, creating a narrative that is satisfying but never comfortable.

Entwined with Ted and spurring the main plot onward is Dee, the woman who moves in next door in the early part of the novel. Dee’s life is in shambles, though not nearly to the extent of her neighbor’s, as she carries a single-minded devotion to the location and identification of the person who kidnapped her little sister, Lulu, during a family vacation years before. With and without reason, Dee’s suspicions settle on Ted, and the novel beds into a tense season of mutual surveillance.

For anyone who was willing and able to isolate during the pandemic, the setting of Last House on Needless Street will feel thematically familiar. The characters spend a great deal of time alone, rarely interacting with each other and typically contacting outsiders via the phone or in arranged meetings. It is very much a novel for our times, and this lends to its tension; any one of us could easily have wound up in another house on Needless Street, passing time no better than Ted and Dee do. We are all perpetually waiting for better, future times–when Ted has found a life outside his home; Dee, satisfaction in the case of her sister’s disappearance; Lauren, escape from Ted, and the life of a normal ten-year-old girl complete with lightning bolt leggings and camping trips; and Olivia, united with her true love, a stray tabby who roams the neighborhood.

The prose in Last House is exceptional, with the style thick and the substance just strong enough to support it. Despite having few settings and many developments which are only consequential as the darker corners of the narrative are exposed, it should prove a steady, engaging read that provokes a great deal of consideration in its wake. Just as the story is potentially growing still, it rises to a very satisfying final act that does a pretty solid job of resolving its admittedly daunting narrative.

Without spoiling things, I wasn’t completely satisfied with the conclusion of the novel for the simple reason that a story should really only have one Norman Bates, and Last House has several, possibly stressing the limits of verisimilitude for some readers. Having multiple characters prove deeply unreliable as a result of their mental trauma feels like painting outside of the lines. It’s the kind of audacious triple-twist that I feel has been popular ever since Gillian Flynn rose to fame, though few authors, including Catriona Ward, do it quite as well. Fortunately, Ward does many other things exceptionally, and this proves more than adequate to balance the novel's quality.

Score: 7.9

Strengths

Exceptional writing

Strong character development

Perpetual, incisive sense of dread and discomfort

Satisfying conclusion

Weaknesses

Tricksy narrative may frustrate some

Some aspects seem implausible when scrutinized

You can purchase this book at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or preferably, through an independent bookstore in your community.

You may also like: Gene Wolfe’s short fiction, This Thing is Starving