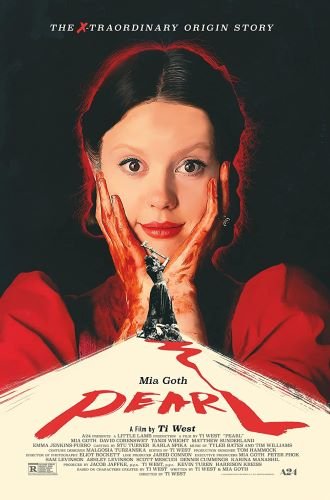

Film Review: Pearl (2022)

A24

Pearl gives the audience a complete picture of its star character in the opening scene: Mia Goth struts across her family’s barn, dancing and chatting with the animals about how she’s going to be a star. She climbs a stack of hay bales and, pitchfork in hand, strikes a starlet’s pose while turning her winsome smile to the camera.

Then, a wild goose wanders into the barn, and, having no purpose there that Pearl can recognize, she unceremoniously impales it on the pitchfork and feeds it to the alligator in the pond. Her smile never falters.

While Pearl has further layers, deeper, more humane, and unexpectedly sympathetic ones, you’ve already seen what you need to in order to grasp the foundation of the character: she’s got a star’s mentality, and believes violence is a wholly natural and effective tool when it comes to meeting the challenges before her.

If We Walk Far Enough

Pearl is a woman apart from the life in which she finds herself. The year is 1918, and while the North Texas farm is a world away from the battlefields of Europe, a global influenza pandemic (unfairly labeled as the Spanish Flu) is affecting every town and city across the nation. Her father is confined to a wheelchair, and her German-born migrant mother is a rigorous disciplinarian who believes her daughter’s only purpose is to serve the needs of family and farm until her newlywed husband, Howard, returns from the Great War. It’s a precarious time for a household that doesn’t have a lot separating them from the bowels of poverty, and from the opening scene, we see the twenty-something Pearl struggle to square the realities of her life with her still-green ambitions.

Pearl isn’t interested in running a farm, and the dream of her parents’ generation has become a durance to her young eyes. Much like main characters in the preceding film in the series, X, she is a dreamer who casts her desires to far off cities where the silver screens shine brighter than all around them. She wants to be a dancer, and kick her legs from the floor lights to the rising curtain before a rapturous crowd who is there to see her. She wants to be loved, to be taken away from the rural banality that is life on the farm.

Pearl’s sole comfort is visiting the local theater, where she watches war films and dance numbers while casually sipping on the morphine sulfate meant for her disabled father. When she has a pivotal encounter with a handsome projectionist who calls himself a bohemian and tells her ‘don’t forget to live your life too’, the door to so much she desires swings ajar.

Shortly thereafter, her sister-in-law, Mitzy, lets her know of a dance troupe audition coming through their town the following week. To get the role means to tour throughout the state, performing in churches, and Pearl sees this as her golden ticket to the wider world.

Between her reluctant attraction to the projectionist and the prospect of having a chance to perform her dance numbers for more than the farm animals, Pearl spirals away from the burdens of the farm, and her inherent instability drives her to suddenly find herself at odds with many of the other characters. By the time it’s all over, the farm will be soaked in blood, and Pearl will be scrambling to keep her world from falling apart.

Her dream is not an uncommon one, and in many ways it is the foundation of many of the success stories we Americans love to reflect on as we measure our own ambitions. Only Pearl has another problem, one she is distantly and naggingly aware of: the violence she employs in her day-to-day life on the farm is one she struggles to draw borders around, and more damning, it is something she finds a distant, indistinct pleasure in. Under duress, even in relatively minor instances, Pearl disassociates from the events around her, folding into herself and rapidly justifying her actions while carrying on a personal monologue until the moment has passed.

A New Direction for West

Pearl sees writer/director Ti West return to make a prequel about the primary murderer from his 2021 film X, in which a group of amateur pornographers lodge at a Texas farm and are subsequently murdered by the elderly host and his wife, Pearl. It was a solid, if mishmashed film that presented a lot of thematic and sociological comment without much engagement. Pearl is something wholly different, zooming in whisper-tight on the personal psychological struggles of the title character. Whereas the previous film was largely external to the characters, here audiences will stay tight to Pearl throughout the story, and it creates a spiritually different–and I think superior–film.

Almost everything about the story can be analyzed through the behavior of the main character, and Pearl is almost a wholly different persona depending on whether she is alone or with others, even those she trusts. By herself, Pearl is typically bright and optimistic, experiencing life in vivid extremes of emotion and sensuality. It starts with imagining dance performances in the barn, but escalates to simulating sex with a scarecrow. Alone, she is almost girlish with joy, while with others, it feels Pearl is perpetually in a state of anxious searching for the most intensified conclusion of the encounter. She pinches her father’s finger, and when getting no reaction, proceeds to choke him until he cries. In every instance, Pearl must wring out the full extent of experience; there are no half-measures or accommodations for uncertainty, and this is ultimately why she is inescapably a murderess. Pearl’s mind simply cannot leave understanding to chance.

At the heart of the film is Pearl’s internal struggle, and it can be viewed from two opposing vantages. Either her inborn desire to be seen and appreciated is toxic, and her own psychological instability renders her unable to manage this need in a realistic way, or Pearl simply carries a natural propensity for violence and the incongruencies of the hand she was dealt are so incompatible with her being that she inevitably goes off the rails. There’s a belief that people should always be able to maintain control no matter what they face, but what thing in nature has no limit to the force it can withstand? While there’s certainly no justification for wanton murder, I found Pearl to be a deeply sympathetic character, and recognized her own need to be creatively validated in myself.

I also can’t wrap this review without mentioning the cinematography, and how it goes beyond being aesthetically pleasing and actually serves the psychological themes of the film. Every set is an amalgamation of extremes: fire-engine reds, stark whites, summer-sky blues and fecund greens. The colors are heavily saturated, reminiscent of Technicolor, so vibrant and contrasting that they would probably look just as sharp in black-and-white. The interior lighting in the film is unnatural, like a stage play, and the cumulative affect is to lacquer the scenes in a dream-like vision, almost as if Pearl’s eroding psychology were transposing the Texas farm onto the stage where she is the star of major production. It’s the kind of effect some filmmakers do just because they can, but here it serves to color Pearl’s world as she likely sees it.

Solving for X

For much of the film, I was bothered by Pearl’s motivations, as they seemed inconsistent with what drives her in X. Here, she is driven to seek recognition by the wider world, envisioning herself as a dancing starlet who appears on movie screens across the country. Yet Pearl’s speech to Mitzy in the penultimate chapter of the film validates her transition from someone who seeks fame to someone who wishes to be cherished and recognized as a sexual being. When she seeks reconciliation with Howard, Pearl acknowledges her perceived shortcomings and becomes willing to make amends by becoming the ideal farmer’s wife that he wants, if he in turn promises to accept her and never leave her alone again.

Regardless of what one feels about how it ultimately manifests, this is a powerful message. All of us want to be loved and accepted by those we value, and we want our loved ones to meet us where we are—or perhaps more likely—bend to meet us at the full extension of our efforts. I think some viewers will begrudge Pearl for sacrificing her dreams on the altar of something so disdained in our modern world as domesticity, but I saw this as a tremendous and utterly human act, a willingness to acquiesce and become what Howard wanted if he would in turn meet her needs.

The film closes with Howard returning home and walking into a grisly scene where Pearl has set up her dead parents at the dinner table around a rotting pig. Both corpses are in an advanced state of decay, and the food around the table is spotted with mold. Pearl enters the scene and the credits roll as Mia Goth gives one of the most intense non-verbal performances I’ve seen in a horror movie.

Given what we know from X, we can presume that Howard accepted Pearl where she was, just as she wanted, and helped her to clean up the scene and return to some newly realized normalcy. They lived out their days on the farm, Pearl finding her newfound edification and validation through sexual and companionable connection to her husband, at least until another sixty-one-years passed and a band full of would-be pornographers showed up to rent their bunkhouse.

I believe Pearl is a superior film to its sequel predecessor, telling a bloody but heartfelt story of a young woman who struggled to find her place in the world and bear the starkness of the hand that life dealt. Despite her faults, her outbursts, her patent instability, I felt a tremendous level of sympathy for the title character, and find her only real sin is that of ambition and human need which by its very appetite demanded more than what a North Texas farmer’s life could provide.

Verdict: 9/10

Strengths:

Exceptional cinematography that supports the themes of the story

World-class performance from Mia Goth, who I believe becomes a certifiable horror icon with this film

Tight, complete story that connects the younger Pearl with the elderly woman we meet in X

Is the perfect prequel in that it supports what comes later without being dependent on it to create a story

Weaknesses

Character links between films may be slightly imperfect, but we’re also missing sixty years of the story.